Hello, Dirtbag Nation!

I don’t make a habit of inviting guest authors into this newsletter, mostly because it’s my space to let my inner garbage raccoon run free. However! When my dear friend Mary McMyne told me she was working on a book she described as “queer Dark Lady from Shakespeare’s sonnets gets literary revenge on her slanderer,” I essentially kicked down her door to get my hands on an advance copy.

And Mary portrays Dirtbag Shakespeare in such an absolutely perfect way that I wanted to invite her on to chat with me about those wacky Elizabethans we all know and love. Thus was DTTA’s first interview born!

Mary’s book is called A Rose by Any Other Name, and it’s available today in the US and Canada and on July 18 in the UK. You should use those links to buy it. This is the unbiased Dirtbag Nation stamp of approval.

As if you needed more convincing, there is a historically accurate cat in the book and she is a Very Good Girl. Moreover, there is a painting of this cat where she looks so much like my cat, attitude included, that I have no choice but to show you a side-by-side:

We’ll be back to our previously scheduled programming next week, but for now, please enjoy this conversation between me and Mary!

Allison: First of all, you know I’m obsessed with this book, so thank you for writing it for me specifically.

I’m sure you’re tired of answering this question by now, but not all members of Dirtbag Nation are English majors, so let’s set the stage first. Who was the Dark Lady? Was she a real person? What do we know about her?

Mary: The “Dark Lady” is the name of a mysterious character with raven-black hair and eyes, who appears in the collection of 154 sonnets Shakespeare wrote during the 1590s. Some of them are gorgeous love poems… others are more like hate poems. The first 126 are addressed to a “Fair Youth,” a beautiful young man with light eyes and hair, and the next 26 or so are about the so-called “Dark Lady.”

We don’t know if the Fair Youth and Dark Lady are based on people Shakespeare loved in life, but there is a lively train of speculation about who they could have been, ever since the sonnets were first published and dedicated to a mysterious Mr. W. H. in 1609.

A Rose by Any Other Name is me jumping on that train.

If you read the sonnets in the order in which they were first published, a tempestuous story emerges. The Fair Youth sonnets start off trying to convince the young man to marry, but at Sonnet 18, something changes. The speaker starts writing him love poems, over a hundred of them.

I love most of the Fair Youth sonnets, but once you hit the Dark Lady sonnets, the tone becomes uneven. Some of them are beautiful and romantic enough to give you chills, but others are cruel, misogynistic. They accuse his mistress of being morally corrupt. They claim she broke her “bed-vow,” stole the Fair Youth away from him, and gave both he and the Fair Youth venereal disease. They imply her power over him may have come from the devil.

There are actual scholarly articles about the connections Shakespeare makes between vaginas and hell. I wish I was joking.

Allison: No yeah, I vividly remember the hell-vagina conversation from my college Shakespeare classes. This is not the only time it comes up. There’s a whole scene where King Lear yells at his daughters’ hell-vaginas.

Anyway.

A Rose by Any Other Name reimagines the Dark Lady as an outspoken, flirtatious, reckless woman who cares deeply for many things: her family, music, freedom—and her best friend Cecely. Talk to me about sapphic representation in the Elizabethan age?

In my experience, historical lesbians have been harder to track down than historical gay men, partly because history focuses on male stories, partly because the church could not fathom how women might have sex without a penis and so didn’t even bother making it illegal.

Mary: So Valerie Traub wrote this fabulous book, The Renaissance of Lesbianism in Early Modern England, which looks for evidence of lesbian desire not in law or history, which basically ignores it for the reasons you note, but in language, literature, pornography, drama, visual arts, and medicine. From Traub, I learned that while words for sexual orientation categories like “gay” or “lesbian” didn’t exist during this period, words for those who performed queer acts did. It turns out the French word for a woman who sought out sexual pleasure with another woman was assimilated into English right around the year 1600, and references to sexual acts between women can be found in period engravings, letters, paintings on castle walls, and in Shakespeare’s plays.

For years, my favorite Shakespeare play was As You Like It for exactly this reason!

Allison: Your author’s note includes one of my favorite William Shakespeare anecdotes. Richard Burbage had just finished a production of Richard III and was about to celebrate by taking essentially a theater groupie to bed. However, Will got to the rendezvous point first, slept with the groupie, and when Burbage yelled at him from the foot of the stairs, sent down a note that read “William the Conqueror came before Richard III.”

In other words, DIRTBAG SHAKESPEARE!!

How did you approach writing Shakespeare in A Rose by Any Other Name? Did you have any worries about creating a messy, self-destructive, sexy dickhead out of someone as famous and revered as The Bard?

Mary: At first, I was just stupidly excited that my publisher put “Dark Lady book” in my contract, because I had been wanting to read the queer story behind the sonnets since I was a teenager. As a lifelong Shakespeare nerd, I’ve always had this picture in my head of what young Shakespeare was like—brilliant and witty, sexy and empathic, but also deeply arrogant and insecure—and I was excited to write him that way. But when the smoke cleared and I finally sat down to do it, I got really intimidated.

I reacted to this anxiety by reading every Shakespeare biography I could get my grubby hands on, cross-referencing critical editions of the sonnets, and re-reading and watching the early plays. What I read confirmed that my vision of him was a real possibility. The sonnets are hella misogynistic, early plays like Taming of the Shrew are problematic, and—while Shakespeare did better with writing women characters later in life—his early work definitely makes sense in the context of Dirtbag Shakespeare.

Allison: I have to ask you about your opinions on the Anti-Stratfordians. I feel like I know what they are. But I still have to ask.

Mary: For the non-English majors, the Anti-Stratfordians are the people who claim that the historical William Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon could not have been the person to write his plays. “He wasn’t educated enough!” they say. “He didn’t go to college! He couldn’t have been such a genius!”

Allison, becoming increasingly incensed: “Maybe Kit Marlowe faked his death, ran away to France for five years, and then snuck back into London to write plays where he embedded coded references to his own works, like every smart person would do if they were trying not to be discovered by the Elizabethan secret service!!!”

Mary: It’s my understanding that approximately 99.99% of Shakespeare scholars think William Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays, and that he could’ve gotten the knowledge to write them from a typical Elizabethan grammar school education. The truth is Shakespeare got things wrong. He pulled most of his history from a few books. His geography is wonky.

What he’s good at is puns and bawdy humor, witty one-liners, double and triple entendres, beautiful images and metaphors and language.

It is possible to be brilliant and not have gone to Cambridge.

When I think about this question, I always think about the connection between Shakespeare’s son Hamnet and the play Hamlet. About the 1592 pamphlet by a college-educated rival of Shakespeare’s, A Groatsworth of Wit, in which Robert Greene accused “an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers” of imagining “with his tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide” (a reference to Henry VI) that he could write like a college man, accusing him of thinking himself “the only Shake-scene in the country.” That sure sounds like he’s talking about Shakespeare to me!

Allison: You brought up Robert Greene so I am morally obligated, as always, to re-share this woodcut of him in his funeral shroud (which all sources tell me is not a tamale wrapper but I have eyes):

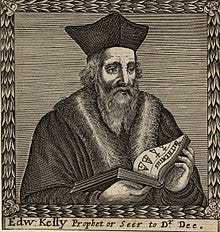

Also! John Dee is in this book! AKA Dirtbag Number One! Talk to me about your experience researching and writing about the Dees. I learned things about him and Edward Kelley while reading your book that I did not know, including a deeply upsetting version of Elizabethan Wife Swap.

Mary: One of the first books I read for this novel was John Dee’s Conversations with Angels, in which Deborah Harkness describes Dee’s séances with his scryer Edward Kelley. As it turns out, Edward Kelley was the biggest grifter who ever grifted. He was imprisoned multiple times for falsely advertising that he knew how to transmute lead into gold. He dragged Dee and his whole family across Europe in pursuit of sketchy occult knowledge before he finally died in a Bohemian castle prison.

According to one 19th century writer, Kelley tricked Dee into believing an Angel had commanded them to share everything, including their wives.

Allison: WHY DOES THIS KEEP HAPPENING IN HISTORY I SWEAR TO GOD PEOPLE WILL BLAME EVERYTHING ON “AN ANGEL MADE ME DO IT”

Mary: Supposedly, Dee was reluctant to agree at first—

Allison: I FUCKING BET HE WAS!!

Mary: —but later became convinced the recommendation was authentic and coerced his wife to go along with it. The story goes that nine months later, Jane Dee gave birth to a baby who may have been Edward’s. I have been unable to confirm this story elsewhere, but I did find a cryptic diary entry from Dee around the right time referring to “a certain kind of recommendation between our wives.”

As soon as I read that story, I knew I had to include Jane Dee’s perspective on the incident in the novel. Jane ends up becoming one of Rose and her mother’s clients.

Allison: Speaking of Rose’s mother!! I can’t let you go without asking about Katarina Rushe, the mother of your Dark Lady who works as a healing witch and is the dictionary definition of “gaslight gatekeep girlboss.” Her schemes and magic give me Catherine de Medici vibes in the best way. What inspired you when creating her character? Who else should I read about in history if I love this woman?

Mary: One of the conceits of my novel is that Shakespeare’s plays contain references to his relationship with Rose. She and her mother, together, are supposed to be the inspiration for Katarina in Taming of the Shrew, which Will would’ve written a couple years after he and Rose broke up. In one scene, Rose tells him how shrewd her mother is, and Will pauses to make a note. But Katarina Rushe only truly came to life when I started imagining the choices a widowed, disowned, Italian-Catholic witch might have to make to support her family in 16th century England. Katarina is terrible, but also, of course she is! Look what she’s up against.

Catherine de Medici is an excellent comparison, but honestly, I think every powerful woman in history has something in common with Katarina. To write Hildegard of Bingen for my last novel—

Allison, loudly interrupting: RED ALERT: MY HOMEGIRL HILDEGARD VON BINGEN HAS BEEN MENTIONED!!!

Mary, politely pretending Allison has an ounce of decorum: —I read everything she had ever written that had been translated into English, including her letters to the Pope and Emperor. Hildegard was a saint, a gifted healer, abbess, visionary, and musician. But she was also a brilliant rhetorician—and a master manipulator. If she hadn’t been, she never would have been granted enough power to obtain the influence for which she became known.

Allison: OK, Last question. If you could challenge one historical figure to a fistfight in the street, who would it be? (Assume for the sake of the question that you would win no matter what.)

Mary: Edward Kelley.

Again, the book is A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME, available wherever books are sold in the US/Canada on July 16 and the UK on July 18.

Thanks for joining me in this super-special bonus newsletter! I’ll be back next week with your regularly scheduled programming.

-Allison

I finally have the opportunity to comment on Anti-Stratfordians! It gets me every time that Mark Rylance is an Anti-Stratfordian! Yes, Mark Rylance, as in ‘former creative director of Shakespeares Globe’ Mark Rylance. I can’t watch anything he’s in without my brain just going ‘doesn’t believe WS was real’.

What a fantastic piece to read first thing this morning. Am so grabbing all the books! Thank you!